New Year in Japan: Ultimate Guide to Traditions, Food, and Hatsumode

“How do Japanese people celebrate New Year? What’s the meaning behind traditions like Hatsumode and Osechi Ryori? And how can I join in as a foreigner?”

Japanese New Year is a unique blend of ancient traditions and modern celebrations, offering something special for everyone. From visiting shrines at Hatsumode to enjoying Osechi Ryori and exploring customs like Joya no Kane (temple bell ringing) and Nengajo (New Year’s cards), understanding these traditions will help you truly appreciate the season.

This guide covers everything you need to know: the significance of New Year’s traditions, tips for celebrating as a foreigner, and how to make the most of modern customs like fukubukuro (lucky bags). Whether it’s your first time experiencing Japanese New Year or you’re looking to deepen your cultural understanding, this article is your ultimate resource!

Understanding Japanese New Year Traditions

The Historical Importance of New Year in Japan

The New Year, or 正月 (Shogatsu), holds a profound significance in Japanese culture, serving as one of the most important cultural celebrations of the year. Historically, the Japanese New Year was based on the lunar calendar, but since the late 19th century, it has been celebrated according to the Gregorian calendar, just like in the Western world. The traditions surrounding Shogatsu are deeply rooted in 神道 (Shinto) and 仏教 (Buddhist practices), underscoring the importance of purification and renewal.

The Japanese New Year celebration, known as 正月 (Shogatsu), traditionally spans from December 31st to January 3rd, though preparations begin much earlier. The period is marked by several significant dates:

- December 31st (大晦日, Omisoka): The final day of the year

- January 1st (元日, Ganjitsu): New Year’s Day

- January 1-3 (三が日, Sanganichi): The first three days of the year

Historically, New Year customs have been meticulously maintained to ensure good luck and prosperity for the coming year. For instance, houses are thoroughly cleaned before the New Year to symbolize the removal of misfortune, which is known as 大掃除 (Osoji). Symbolic decorations such as 門松 (Kadomatsu) and しめ飾り (Shimekazari) are used, each carrying its own significance of warding off evil spirits and welcoming ancestral deities.

Traditionally, on New Year’s Eve, families would gather to share a meal and listen to the 除夜の鐘 (Joya no Kane) ringing from Buddhist temples, where monks toll the bell 108 times to represent the cleansing of 108 earthly desires. This ritual promotes a clean slate for the New Year, fostering a sense of peace and reflection.

How Traditions Have Evolved Over Time

While many of these customs have been preserved, modern influences have shaped how the Japanese celebrate the New Year. Today, it’s common to see a blend of traditional and contemporary practices, yet the spirit of 正月 (Shogatsu) remains unchanged—focusing on family gatherings, rest, and reflection. In the past, New Year festivities were mostly private family affairs, but now they have expanded to include more communal celebrations. Despite the introduction of some Western customs, such as countdowns and fireworks in urban areas, the essence of traditional Japanese values persists. During Shogatsu, the first three days of January (三が日, Sanganichi) are still reserved as important family time, where many Japanese take the opportunity to return to their hometowns and reconnect with relatives, maintaining the age-old traditions of unity and renewal.

Japanese New Year Traditions for Good Luck

Specific traditions during the Japanese New Year are believed to bring good luck and ward off bad fortune. Lucky charms, or 御守り (Omamori), are often purchased from shrines or temples for personal protection and prosperity. Many people will participate in 初詣 (Hatsumode), the first shrine visit of the year, to pray for health and happiness. It’s customary to make wishes and drink 甘酒 (Amazake), a traditional sweet drink.

Moreover, the practice of 鏡開き (Kagami Biraki), which involves breaking open a sake barrel 酒樽 (Sakadaru), is part of New Year celebrations and symbolizes the sharing of joy and harmony. The careful observation of these traditions ensures that individuals and families start the year on the right foot, pursuing harmony and balance in their personal and professional lives.

Japanese New Year Decorations: Meaning and Use

Decorations play a significant role in the Japanese New Year, being both aesthetically pleasing and symbolically powerful.

門松 (Kadomatsu), composed of pine, bamboo, and plum (松竹梅, Shouchikubai), are placed at the entrance of homes and businesses to invite the gods of good fortune. These elements—pine (松) for longevity, bamboo (竹) for resilience, and plum (梅) for new beginnings—embody the core wishes for longevity and prosperity.

Kadomatsu are typically set up after Christmas, around December 26th, and remain in place until January 7th. However, they are traditionally avoided on December 29th and December 31st due to superstitions:

- December 29th: The number “29” sounds like “double suffering” or 二重苦(Nijuku) in Japanese, which is considered unlucky.

- December 31st: Decorating on this day is called ”一夜飾り (Ichiya kazari)” and is considered last-minute and disrespectful to the gods.

しめ飾り (Shimekazari) is a traditional Japanese decoration used during the New Year. Shimekazari is typically hung at the entrance of homes and shrines to welcome the 年神様 (Toshigami sama), the deity of the New Year, and to ward off evil spirits. This decoration signifies the purification of the space and the invitation for good fortune to enter.

Shimekazari typically consists of several key components. The first is しめ縄 (Shimenawa), which is the main straw rope that acts as a boundary to ward off evil spirits. Attached to the shimenawa are paper strips known as 紙垂 (Shide), which enhance its sacredness. Additionally, shimekazari often features greenery, including 裏白 (Urajiro), a type of fern, and sometimes citrus fruits like 橙 (Daidai), which symbolize prosperity and the continuity of family lineage.

Shimekazari is typically displayed starting from December 13, known as 正月事始め (Shogatsu hajime), which marks the beginning of New Year preparations. Here are some key points regarding the timing:

Ideal Display Period:

- December 13 to January 7 (or 15): It is common to hang shimekazari during this period (Varies by region).

- Avoid December 29: This day is considered unlucky because the number “29” sounds like the Japanese word for double suffering (二重苦, Nijuku).

- Avoid December 31: Hanging decorations on this day, which is called 一夜飾り (Ichiya kazari), is seen as disrespectful to the gods, as it is considered a last-minute effort.

The period for displaying New Year’s pine decorations is called 松の内 (Matsu no Uchi), and it varies by region. Generally, it starts from 正月事始め, the beginning of the New Year celebrations, and lasts until January 7 in the Kanto region and until January 15, known as 小正月 (Koshogatsu), in the Kansai region. During this time, it is believed that the deity of the New Year, or 年神様 (Toshigami sama), stays in the home, marking the period from the start of the New Year celebrations until the deity’s departure. Once 松の内 (Matsu no Uchi) is over, the New Year’s decorations are taken down, and people eat 七草粥 (Nanakusa gayu), a rice porridge with seven herbs, to care for their stomachs after the feasting of the New Year.

The Significance of Hatsumode: The First Shrine Visit

Preparing for Hatsumode

初詣 (Hatsumode), the first visit to a shrine or temple in the New Year, is a deeply entrenched tradition that holds great significance in Japanese culture. This custom is not only about prayers and blessings but also symbolizes a fresh start as people seek divine protection and good fortune for the year ahead. As New Year’s Eve approaches, families prepare for this important event by donning their best attire, often traditional kimono, which adds to the solemnity and cultural richness of the occasion.

In preparation for Hatsumode, many people also purchase new amulets (御守り, Omamori) for protection and good luck in areas such as health, academics, and relationships. Before entering the shrine grounds, it is customary to cleanse oneself at the 手水舎 (Chozuya), a purification station featuring flowing water. The ritual involves rinsing one’s hands and mouth to purify the body and spirit before approaching the deity.

Popular Shrines and What to Expect

Japan boasts an abundance of shrines and temples, each with its unique history and significance. Some of the most popular destinations for Hatsumode include 明治神宮 (Meiji Shrine) in Tokyo, 伏見稲荷 (Fushimi Inari Taisha) in Kyoto, and 住吉大社 (Sumiyoshi Taisha) in Osaka. These locations are known for their vibrant atmospheres, attracting millions of visitors during the first few days of January.

Tokyo

明治神宮 (Meiji Shrine)

Meiji Shrine is a shrine dedicated to Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken, and it attracts many visitors for Hatsumode (the first shrine visit of the year) every year. Especially on New Year’s Day, it is known for having one of the highest numbers of visitors in the country, leading to significant crowds. Meiji Shrine is located near Harajuku Station and is surrounded by a vast forest, providing a tranquil environment that is appealing to visitors.

Kyoto

伏見稲荷 (Fushimi Inari Taisha)

Fushimi Inari Taisha is the head shrine of the approximately 30,000 Inari shrines across Japan and attracts the most visitors in the Kinki region during the New Year’s holiday period. It is particularly popular, with entry restrictions in place at midnight on January 1st due to the large number of visitors. The shrine is famous for its thousands of vermilion torii gates, making it a popular spot for tourists.

Osaka

住吉大社 (Sumiyoshi Taisha)

Sumiyoshi Taisha is the head shrine of over 2,000 Sumiyoshi shrines across the country and is believed to bring good fortune, ward off evil, and promote business prosperity. Many people visit for Hatsumode, especially those wishing for success in their businesses.

When visiting a shrine for Hatsumode, you’re likely to encounter long lines of people waiting patiently for their turn to pray. Once at the main hall, visitors offer coins, customarily 5 yen, believed to be auspicious as it represents good fortune, and perform a series of bows and claps, completing their prayers with a respectful bow.

Proper Hatsumode Etiquette

At the Entrance:

- Pass through the 鳥居 (torii) gate with a slight bow

- Avoid walking directly in the center of the path, as this space is traditionally reserved for deities

- Cleanse your hands and mouth at the 手水舎 (chozuya) water pavilion

At the Main Hall:

- Make your prayer or wish

- Make a monetary offering (typically 5 yen for its auspicious sound in Japanese)

- Bow twice deeply

- Clap twice

- Bow once more deeply

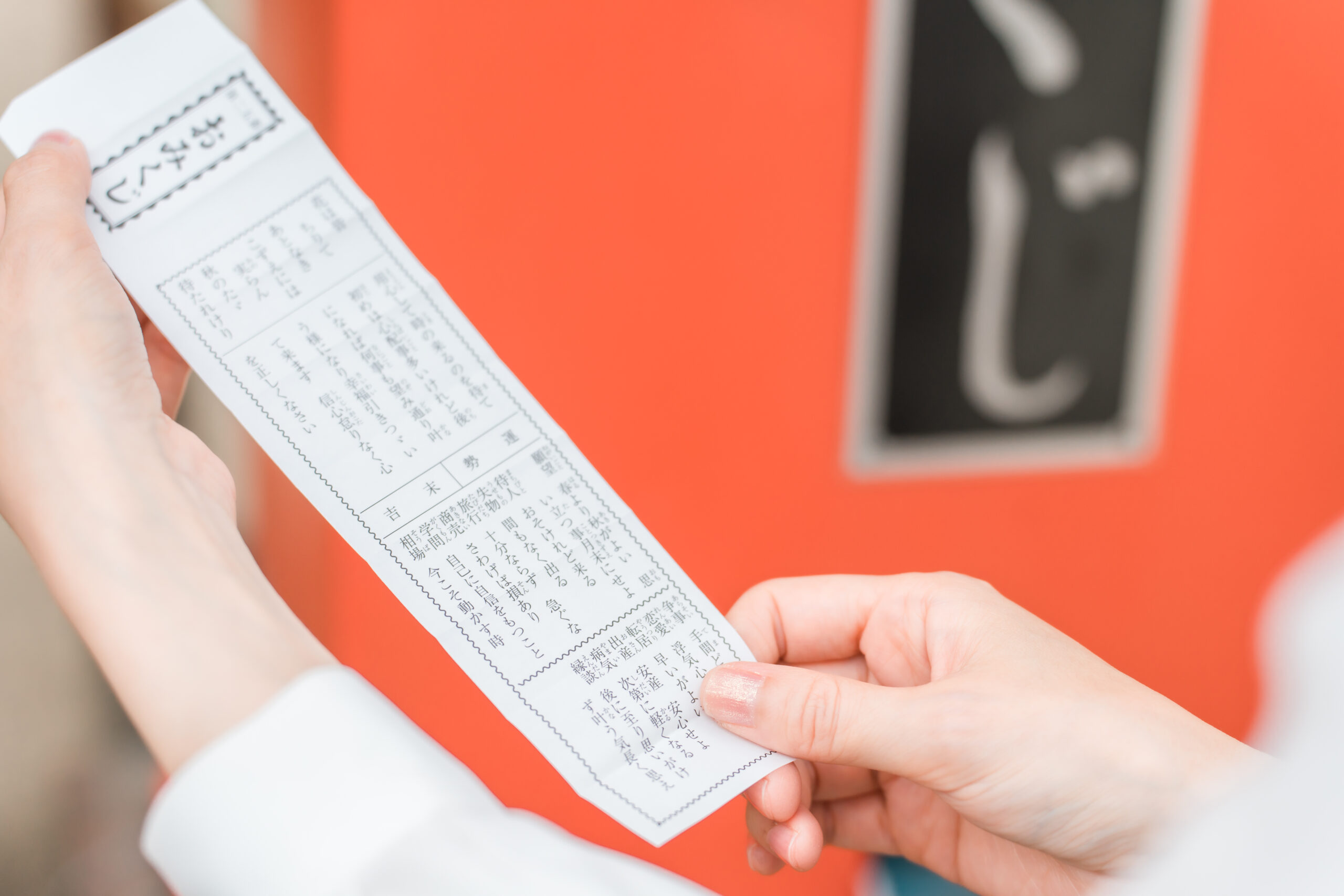

Shrines often host a variety of stalls selling food, traditional charms, and おみくじ (Omikuji, fortune-telling paper slips), that range from 大吉 (great blessings) to 凶 (curses). Should one receive a negative fortune, it can be tied onto designated racks within the shrine grounds, symbolically averting bad luck.

A Guide to Things to Do on New Year’s Day in Japan

初詣 (Hatsumode) offers a rich tapestry of activities beyond the central prayer ritual. Many shrine-goers take part in drawing their first omikuji for a glimpse into the coming year. The diversity in 御守り (Omamori) provides a unique opportunity to tailor one’s prayers with various charms catering to specific needs, whether for career success, safe travel, or family harmony.

Additionally, during Hatsumode, one can engage with the cultural practice of purchasing 破魔矢 (Hamaya), or “demon-breaking arrows,” which are thought to dispel malevolent spirits and bring peace and good luck. These decorative arrows are often beautifully crafted and make for meaningful New Year symbols.

Food stalls add a festive layer to the experience, offering visitors a chance to indulge in Japanese traditional treats like たこ焼き (Takoyaki), お好み焼き (Okonomiyaki), and 団子 (Dango). The lively atmosphere, coupled with the aroma of street foods, enhances the overall experience, allowing individuals to connect with others and partake in communal joy.

Hatsumode is, therefore, a multifaceted event that goes beyond mere prayer. It embodies the themes of reflection, renewal, and community, where individuals, families, and visitors alike can participate in a convivial setting, welcoming the New Year with open hearts and hopes for a prosperous future.

Best Times for Hatsumode

The most traditional time for hatsumode is during 初日の出 (hatsuhinode, first sunrise) on January 1st. However, visiting times have become more flexible in modern Japan:

Peak Hours to Note:

- Midnight to sunrise on January 1st (most crowded, most traditional)

- January 1st daytime (extremely crowded)

- January 2nd-3rd (moderately crowded)

- January 4th-7th (relatively quiet)

Culinary Delights: Osechi Ryori and Other New Year Foods

The Symbolism Behind Osechi Ryori

御節料理 (おせち料理, Osechi Ryori) is an intricate and beautifully arranged array of traditional Japanese New Year foods, each dish and ingredient laden with auspicious meanings meant to bring good fortune, health, and prosperity for the coming year. Traditionally packed in special tiered boxes called 重箱 (Jubako), these dishes are prepared in advance and enjoyed over the first three days of January, allowing families to rest and relax without cooking.

Each item in Osechi has a symbolic meaning, often indicated by puns or visual associations. For instance, sweet black soybeans (黒豆, kuromame) symbolize diligence and health, while herring roe (数の子, kazunoko) represents fertility due to the multitude of tiny eggs. 昆布 (Kombu, a type of kelp) is tied into knots and symbolizes joy, as the word is related to the term 喜ぶ (yorokobu), meaning happiness.

田作り (Tazukuri, dried sardines) represents prayers for a bountiful harvest, 紅白かまぼこ (Kohaku kamaboko, red and white fish cake) symbolizes congratulations and good luck, and 栗きんとん (Kurikinton, candied chestnuts) embodies wealth, nobility, and prosperity.

Beyond its symbolic importance, Osechi reflects Japan’s rich culinary tradition, offering an array of flavors and textures designed to be savored gradually over the holiday period. It is a vibrant representation of seasonal bounty, cultural expression, and family unity.

Making and Eating Toshikoshi Soba

Another culinary tradition is the consumption of 年越し蕎麦 (Toshikoshi Soba) on New Year’s Eve. These long buckwheat noodles signify the passage from one year to the next, with their length representing longevity. In addition, buckwheat, which is easy to cut, also has the meaning of cutting off the hardships and calamities of the year. This dish serves as an edible metaphor for cutting ties with misfortune before the New Year begins.

The art of making Toshikoshi Soba can be a communal family activity, fostering interaction and engagement among family members as they prepare the thin, delicate noodles. Toward the evening of December 31st, families sit down to enjoy this simple yet meaningful dish, reflecting on the past year while looking forward to fresh beginnings.

Enjoying Toshikoshi Soba is more than a culinary experience; it is a mindful practice steeped in gratitude and hope, making it a quintessential element of the Japanese New Year celebration.

New Year in Japan Food: Must-Try Dishes

In addition to Osechi Ryori and Toshikoshi Soba, the Japanese New Year is characterized by an array of delicious foods, each partaking in a tapestry of taste and tradition. 餅 (Mochi), glutinous rice cakes, are a staple during this period, symbolizing strength and fortune. They can be enjoyed in various preparations, including in a savory soup known as お雑煮 (Ozoni), which varies regionally in ingredients and flavors.

伊達巻き (Datemaki), a sweet rolled omelet mixed with fish paste, is another popular Osechi dish, prized for its sweet taste and rolled shape that resembles ancient scrolls, symbolizing knowledge and learning. Similarly, 海老 (Ebi), or shrimp, is included in Osechi for longevity, as its curved shape is reminiscent of an old man’s back, implying a wish for a long life.

A trip to the supermarket or local food market before the New Year is a cultural experience in itself, as the aisles fill with special ingredients and pre-prepared Osechi sets, inviting even novice cooks to explore the culinary tradition. This period is a wonderful opportunity for both locals and visitors to deepen their connection with Japanese culture through its rich and symbolic New Year foods.

These culinary delights underscore the Japanese ethos of respect for tradition, the celebration of life’s blessings, and the hope for renewal and new opportunities. Whether enjoyed in the company of family or shared among friends, these dishes are as much about flavor as they are about togetherness and introspection.

Engaging with Modern Traditions: From Joya no Kane to Fukubukuro

Experiencing Joya no Kane: Ringing the Temple Bells

As the New Year approaches, one of the most tranquil and profound experiences in Japan is witnessing the 除夜の鐘 (Joya no Kane), an annual ritual where Buddhist temples ring their bells 108 times. This practice purifies participants by dispelling the 108 worldly desires or delusions, providing a spiritual cleanse to start the year anew. The chime of the temple bell reverberates through the chilly night air, creating a serene atmosphere that invites reflection and meditation.

During this time, many temples open their grounds to the public, allowing individuals to participate in the bell-ringing ritual. As midnight draws near, people gather silently, bundled against the winter cold, each awaiting a chance to pull the hefty rope that swings the bell clapper.

Exploring Fukubukuro: The Lucky Bag Phenomenon

In contrast to the meditative tradition of Joya no Kane, 福袋 (Fukubukuro), or “lucky bags,” introduce an element of fun and excitement to the New Year’s festivities. Retailers across Japan offer these mystery grab-bags at discounted prices, filled with a variety of goods ranging from fashion items and electronics to household goods and cosmetics. This tradition has been a mainstay since the early 1900s.

Shopping districts and department stores see a significant influx of customers eager to snag a bargain or lucky find, often queuing in long lines well before stores open. For the uninitiated, navigating these sales in busy urban centers can be an adventure of its own, providing a fascinating glimpse into Japanese consumer culture.

How Modern Traditions Complement Traditional New Year Celebrations

While 初詣 (Hatsumode) and 除夜の鐘 (Joya no Kane) offer opportunities for quiet reflection and spiritual renewal, modern practices like 福袋 (Fukubukuro) and New Year countdown events inject energy and excitement into the season. This combination of traditions highlights Japan’s ability to honor its heritage while embracing contemporary culture, creating a celebration that resonates with a wide range of tastes and lifestyles.

The holiday atmosphere beautifully blends the old and the new. Major cities often feature spectacular fireworks displays reminiscent of Western New Year celebrations, drawing crowds who revel in the vibrant colors illuminating the night sky. Additionally, popular music performances and comedy shows broadcast on television cater to younger audiences. This diverse array of celebrations allows individuals to choose how they welcome the New Year, whether through introspective traditions or lively festivities.

Navigating New Year Customs: From Nengajo to Otoshidama

Writing and Sending Nengajo (New Year’s Cards)

年賀状 (Nengajo) or New Year’s cards are a quintessential part of the Japanese New Year tradition, symbolizing gratitude and the exchange of well-wishes. These cards are akin to the Western tradition of Christmas cards, but with a uniquely Japanese flair. Sent to friends, family, and business associates, Nengajo convey messages of happiness and prosperity for the upcoming year.

The art of crafting Nengajo is steeped in personalization and creativity. Many individuals take great care to design their own cards, incorporating themes related to the 干支 (Eto, zodiac) animal of the upcoming year, or incorporating traditional symbols such as 松 (pine), 竹 (bamboo), and 梅 (plum blossoms). This personal touch extends to handwritten notes, making each card a bespoke token of good will.

The Japanese postal service is essential to the tradition of sending 年賀状 (Nengajo) ensuring they are delivered on January 1st. This meticulous coordination creates a sense of community, as millions of people across the country open their cards together, celebrating the New Year with shared joy and well-wishes.

To ensure timely delivery, the cards must be mailed between December 15 and December 25. Each card features the year and a lottery number for the お年玉くじ (Otoshidama Kuji, New Year’s lottery). If someone misses this deadline, it is considered polite to send the card by January 7, which marks the end of the New Year celebration period known as 松の内 (Matsu no Uchi).

The Tradition of Kagami Mochi

鏡餅 (Kagami Mochi), or mirror rice cakes, is a revered Japanese New Year decoration that holds rich cultural symbolism. Composed of two round mochi stacked upon each other, with a small 橙 (Daidai) citrus resting on top. Kagami Mochi is typically displayed as an offering in the household’s 神棚 (Kamidana, Shinto altar) and on 床の間 (tokonoma), a decorative alcove.

The name 鏡 (Kagami), meaning mirror, references the shape of ancient mirrors thought to hold divine powers. Each element of Kagami Mochi is symbolic: the two layers of mochi represent a passing year and the new year, while the daidai, whose name translates to “generation after generation,” signifies the continuity of family lineage and prosperity.

鏡開き (Kagami Biraki) is typically celebrated on January 11 in the Kanto region, where people break the mochi and often use it in soups or desserts. The kagami mochi is believed to be a dwelling place for the deities, and by opening it, families send off the year’s deity, marking the end of the New Year celebrations. Eating the mochi is also thought to bestow the strength to live a year free from illness.

Understanding the Custom of Otoshidama (New Year’s Money Gifts)

A particularly exciting custom for children during the Japanese New Year is receiving お年玉 (Otoshidama), which are money gifts enclosed in small decorative envelopes called お年玉袋 or ポチ袋 (Pochibukuro).

The origin of お年玉 (Otoshidama) lies in the practice of offering rice cakes to the 神棚 (household altar) or 床の間 (tokonoma) during the New Year. The head of the family would then distribute these rice cakes, known as 御歳魂 (Oshoukon), to family members. These rice cakes were considered to embody the life of the year’s deity, and sharing them held a religious significance, as it was believed to ensure a safe and prosperous year for the family. The New Year’s gift changed over time, and what used to be a Kagamimochi was replaced by the gift of money and goods.

お年玉 (Otoshidama) is typically given by parents, grandparents, and close relatives, the amount within these envelopes often reflects the child’s age and the giver’s relationship with them.

New Year in Japanese Language: Essential Guide

New Year Greetings and Phrases

Understanding proper New Year greetings is essential for cultural integration during this important holiday season.

Basic New Year Greetings

Main Greetings:

- 明けましておめでとうございます (Akemashite omedetou gozaimasu)

- Formal New Year’s greeting

- Used from January 1st through early January

- 今年もよろしくお願いします (Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu)

- Expression of goodwill for the coming year

- Often follows the main greeting

Time-Specific Greetings

Before New Year:

- 良いお年を (Yoi otoshi wo)

- “Have a good New Year”

- Used only before December 31st (From mid-December to the 30th)

After New Year:

- 今年もよろしく (Kotoshi mo yoroshiku)

- Casual version of the goodwill greeting

- Used among friends and family

Traditional Expressions Explained

Cultural Phrases:

- 初春 (Shoshun): Early spring/New Year

- 謹賀新年 (Kingasinnen): Written New Year’s greeting

- 迎春 (Geishun): Welcoming the spring/New Year

Seasonal References:

- 初売り (Hatsuuri): First sale of the year

- 初日の出 (Hatsuhinode): First sunrise

Business and Formal Greetings

Professional Settings:

- 謹んで新年のお喜びを申し上げます (Tsutsushinde shinnen no oyorokobi wo moushiagemasu)

- Highly formal New Year’s greeting

- Used in business correspondence

- 本年もどうぞよろしくお願い申し上げます (Honen mo douzo yoroshiku onegai moushiagemasu)

- Formal expression of goodwill

- Appropriate for business relationships

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

The Japanese New Year, or 正月 (Shogatsu), is a beautiful intertwining of tradition, culture, and modernity, offering a wealth of experiences that both celebrate the past and embrace the present. From the solemn sound of 除夜の鐘 (Joya no Kane) to the jubilant exchange of 年賀状 (Nengajo), each custom carries with it the warmth of family, the spirit of renewal, and the hope for prosperity in the coming year.

As we’ve explored, the New Year in Japan is a time for reflection and connection, where customs like 初詣 (Hatsumode) and おせち料理 (Osechi Ryori) not only preserve ancient traditions but also bring people together in a shared experience that transcends cultural boundaries. These festivities offer a glimpse into the heart of Japanese culture.

May the insights and stories shared here inspire you to immerse yourself in the Japanese New Year’s celebrations, welcoming the new year with open arms and a deeper understanding of its meaningful traditions.

Q&A About Japanese New Year

How do Japanese people typically celebrate New Year’s Eve?

New Year’s Eve, called 大晦日 (Omisoka), is marked by the preparation of 年越し蕎麦 (Toshikoshi Soba) and the 除夜の鐘 (Joya no Kane) ritual at Buddhist temples. Many families spend the evening together, watching the popular television program 紅白歌合戦 (Kohaku Uta Gassen) before heading to a shrine for 初詣 (Hatsumode) or relaxing in the comfort of their homes.

What are the most popular New Year’s foods in Japan?

おせち料理 (Osechi Ryori) and 年越し蕎麦 (Toshikoshi Soba) are staples, with Osechi including symbolic dishes like 黒豆 (Kuromame, black soybeans) and 数の子 (Kazunoko, herring roe). お雑煮 (Ozoni), a mochi-containing soup, is also traditionally consumed.

How do I participate in Hatsumode as a foreigner?

Join the crowds at a nearby shrine, observe proper etiquette at the 手水舎 (Chozuya, purification station), and offer a coin before making a prayer. Dressing warmly and respectfully, soaking in the atmosphere, and engaging in the surrounding festivities further enrich the experience.

What are some tips for writing Nengajo?

Personalize your 年賀状 (Nengajo) by including a thoughtful message or artwork that reflects the 干支 (Eto, zodiac animal of the year). Be sure to mail them well in advance to ensure delivery on January 1st.

How do Japanese decorations for New Year differ from Western ones?

Japanese New Year decorations, such as 門松 (Kadomatsu) and しめ飾り (Shimekazari), are deeply symbolic, using natural elements to invite good spirits and prosperity. Unlike the festive lights and wreaths of the West, Japanese decorations focus on simplicity and nature-driven motifs.